d La Repubblica

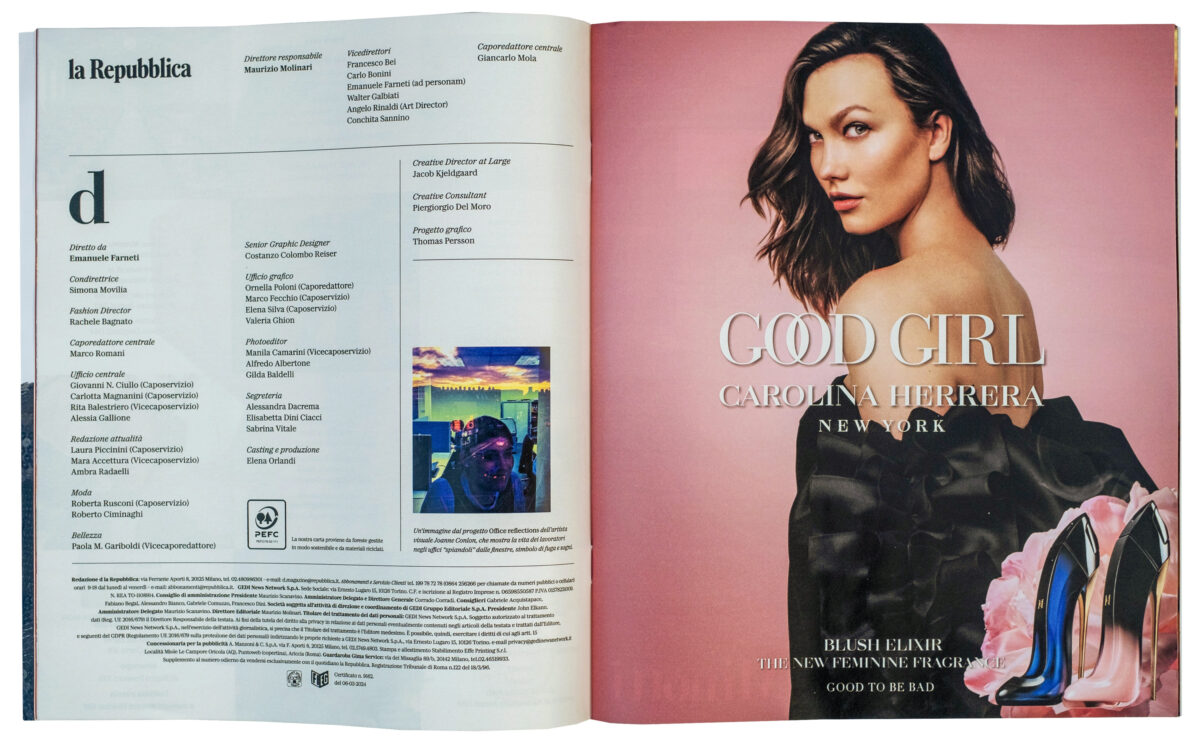

My Office reflections photographs are published in d magazine, La Repubblica newspapers fashion and design supplement

It was a pleasant surprise to receive an email through the contact form on my website, which I initially thought was spam. It was from Alfredo Albertone, the photo editor of the Saturday supplement magazine "d" of the Italian newspaper La Repubblica. They were working on an issue dedicated to work and Generation Z, and he felt my Office reflections series could work alongside the editorial. He had seen my work on the Lens Culture website. I did some research, and he and the newspaper seemingly did exist.

After some back-and-forth communication, Alfredo selected the images he wanted. He was particularly eager to feature one of my images on the cover, and the editorial team agreed it would look fantastic. I was thrilled!

I began this series of photographs in 2012, representing a period of my office working life. I captured reflections of the office in the windows across various floors, merging the outside environment with the office's interior. Now, years later, the office interior has completely changed, and as for the streets outside the Dublin office, well, they are unrecognisable.

Article translated from Italian

Once upon a time, they used to say "lavativi", a word from the old millennium that described those who, in barracks or on a military ship, went around strategically equipped with a broom or rake to give the idea of being busy, while in reality, they were lazing around more than anyone else. Today it no longer means anything, and not only because of the abolition of compulsory military service, but precisely because of the radical evolution - or involution - of the relationship between employees and those who pay their salaries. To photograph the reality of a relationship of "very low intensity conflict" with the world of work, today there are Anglophone lexical innovations: quiet quitting - that is, pulling the oars in a boat while remaining on it - was the big bang from which the universe of coffee badging arose (those who show up at the office only to socialise at the coffee machine), of presenteeism (which is the opposite of absenteeism: remaining attached to the office like mussels glued to one obstacle, but to limit one's contribution to physical presence), or conscious quitting, i.e. the actual farewell to the company when its values do not coincide with the ethical ideal of the worker, a phenomenon that especially concerns the most idealistic generations, such as Millennials and Gen Z.

In addition to all representing a lexical and ideological attack on the dusty - and now heretical - work alcoholism, these words have another common trait: virality. From the outbreak of the pandemic onwards, they have spread forcefully through hashtags on social media, TikTok first and foremost. With a flavour of revanche - the son of digital exhibitionism - never seen before: if until yesterday those who tried to limit themselves to the minimum wage tended to blend in as much as possible among the industrious, now we can talk about "lazy pride".

Or rather, of a joyful renunciation of damning one's soul for one's career, fuelled by likes on social media and by literature that mixes sociology, psychology and doses of irony, see for example, the amusing essay The Lazy Man's Guide to Quiet Quitting: The definitive anti-work guide for anyone who absolutely needs to work less, where there are tasty recommendations for the aspiring quiet quitter. An example? "Try to always give the impression to others that you are busy and have no time to talk to them. This will make you seem in high demand, people will respect you more and leave you alone so you can do your important work. Which of course is fictitious. If someone asks you what you are working on, just say that you are busy. If they ask you to take care of something, you default to: I have a lot to do, but I'll take a look, without saying. What is it that is keeping you so busy?"

There is no shortage of dark sides of the phenomenon, described by as many new words. By rage applying, for example, we mean the tendency to aggressively machine-gun barrages of CVs on the internet in response to an argument with the office manager. In mid-April the New York Post dedicated an article to resenteeism: «This is the condition of someone who is dissatisfied with their job, but doesn't believe they have the possibility of changing it and therefore not only reduces their commitment to a minimum, but harbors resentment because they feel trapped», explains James Detert, professor of management at the University of Virginia, «There is, however, an aspect to which we must pay close attention when we analyse the new language that describes the current way of experiencing work and that is the fact that words are never neutral. In many cases, they express, albeit covertly, the worldview of those in power. Let me explain: defining a quitter as someone who doesn't want, more than legitimately, to kill himself with work is equivalent to branding him as a loser, a slacker. However, this is the language of power, which is why I suggest the use of another neologism, less full of prejudices: calibrated contributing. Maybe it sounds worse, but it allows the issue of dissatisfaction to be addressed in a constructive way: if with words you already place all the blame on the employee, you remove responsibility from the manager and the company culture, discouraging them from finding solutions that can improve everyone's work.

The phenomenon is, however, widespread in Italy even more than in the rest of Europe. «The authoritative research company Gallup tells us that in our country 26% of workers over 40 and 18% of workers under 40 feel "openly hostile" to their jobs. A difference between generations that is also reflected in another Gallup data, the one that investigates satisfaction: only 8% of under 40s and 4% of over 40s feel "fully satisfied". Looking abroad, we discover that the Italian average (6%) is less than half that of Europe (13%) and almost a quarter of that of the world (23%)", explains Paolo Lacci, professor of human resources management at the University of Milan, former long-time industrial manager and author of the recent essay I quit when I want: work in the new millennium between quiet quitting and organisational silence (Egea editions). But didn't common wisdom hold that millennials and Gen Z were more dissatisfied than their senior colleagues? «These data tell us exactly the opposite, but the error is easily explained by the fact that young people are the users of the social media where quiet quitting goes crazy, and therefore they are overrepresented», continues Lacci.

Even though the megaphones are Instagram and TikTok, the fact that we are increasingly talking about quiet quitting and the constellation of its derivatives is not just a superficial trend. «It is rather a symptom of how much the relationship between the individual and the organisation has changed today.

Thirty years ago, before digitalisation and globalisation, people changed jobs a couple of times in their professional life: today it happens on average 6-8 times. The old relationship of mutual trust between employee and company has become a more dynamic relationship of mutual benefit, which lasts only as long as it lasts. These days, the "I make sacrifices today to feel good tomorrow" argument no longer applies, instead "I want to feel good immediately" applies instead.

And then two important psychological factors come into play: «The threshold for tolerating frustration has been greatly lowered: certain attitudes that ten years ago were accepted within an office are no longer accepted today, neither by the boss nor by colleagues», clarifies Lacci. «The word "happiness" has entered forcefully into discussions about work, until a few years ago it was completely absent. Today, precisely because "there is no certainty about tomorrow", people's legitimate ambition has become to be happy now." What if the work context doesn't allow it? I stop whenever I want.